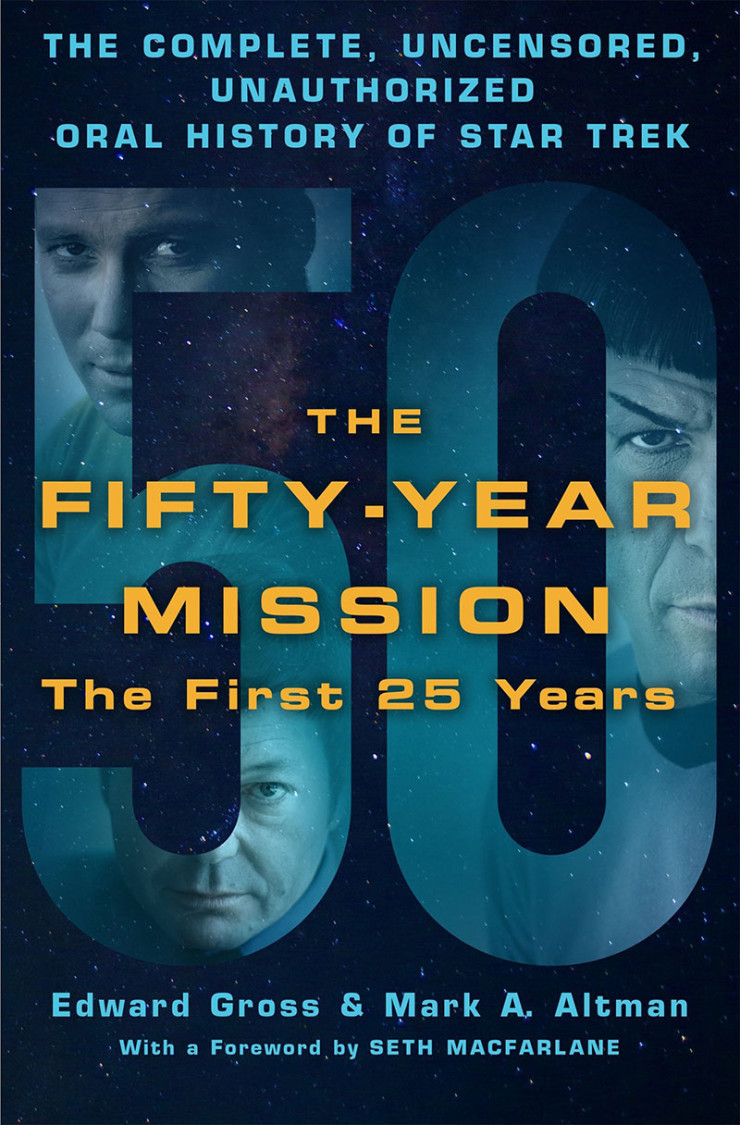

Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman’s The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years, out now from Thomas Dunne Books, is the unauthorized, uncensored and unbelievable true story behind the making of a pop culture phenomenon; a no-holds-barred oral history of five decades of Star Trek, told by the people who were there.

In the below excerpt, learn about Star Trek: Planet of the Titans, one of many attempts at a relaunch through the beloved feature films.

Oddly, Planet of the Titans was not the first movie pitch to suggest that Kirk, Spock, and the crew should…well, you’ll see.

COSMIC GODS

There were many fakata (a Yiddish word that describes the sheer lunacy and strangeness of a notion better than any other word that comes to mind) ideas for Star Trek movies over the years. It began with Gene Roddenberry’s The Cattlemen; about sentient cows on a distant planet being harvested for meat by intergalactic space ranchers; and continued to the infamous trip through the Guardian of Forever in which Spock phasers Kennedy on the grassy knoll; to Harve Bennett’s The Academy Years, a pre-J.J. Abrams prequel. But perhaps the most heady and aspirational mind trip of them all, and sadly unproduced, was Philip Kaufman’s Planet of the Titans. Developed in the mid-70’s until Paramount put the kibosh on it, Kaufman’s Spock-centric take on the franchise would have been a 2001-infused cerebral take on Star Trek that would have sent the franchise trekking in a very different direction. Fascinated? So were we when writing our massive tome covering fifty years of Star Trek, here’s what we—and those most involved in its conception—had to say.—Mark A. Altman & Edward Gross

Perhaps the greatest “what if” in the history of the franchise is auteur Philip Kaufman’s (The Right Stuff, Invasion of the Body Snatchers) proposed Star Trek feature film, Planet of the Titans, which featured a script from British screenwriters Chris Bryant and Allan Scott (whose credits included the acclaimed Nicholas Roeg film, Don’t Look Now), later rewritten by Kaufman himself. While the British screenwriters came to America, Gene Roddenberry was about to leave the country for Britain to shoot his supernatural Spectre pilot.

Despite not even having completed a script, the writing team was already being asked to attend Star Trek conventions, prompting the two writers to ask Roddenberry what to do. His response: “Forget it! Trekkie teeny-boppers lurk outside your room at night yearning to meet you and talk about science. If you must go to one of these, our main concern is that you keep your fly zipped up while on platform.”

Star Trek was viewed as a priority at Paramount, particularly after the first space shuttle, originally called the Constitution, was re-named the Enterprise. This prompted Paramount to take out a full page ad in the New York Times proclaiming, “Starship Enterprise will be joining the Space Shuttle Enterprise in its space travels very soon. Early next year, Paramount Pictures begins filming an extraordinary motion picture adventure—Star Trek. Now we can look forward to two great space adventures.” Ironically, neither would ever take off.

DAVID V. PICKER (President of Motion Pictures at Paramount Pictures)

Of all the films I developed, acquired or greenlit while I was at Paramount, there was just one project that I was simply not interested in: Charlie Bludhorn’s favorite—a movie based on Star Trek. Obviously, character and story are the main ingredients, and in this show the futuristic but accessible world that was portrayed played an important role. But I disliked sci-fi. I didn’t like sci-fi books, movies, comic strips… none of it. Had George Lucas done American Graffiti for us at UA, I believe I would have passed on Star Wars. Jeffrey [Katzenberg] became Barry Diller’s assistant after my departure, and I told Barry that as my parting gift to him, Jeffrey would get Star Trek made. Of course, he did.

GERALD ISENBERG

I was brought into Paramount because I made a deal with Barry Diller and that deal said that if a movie of Star Trek is made, I’m going to be the producer. David Picker, who was the head of the studio at the time, and I hired Phil Kaufman to direct and write. Phil was very taken with the Spock character and Leonard [Nimoy], and thought that a lot of the other characters were past their usefulness. We began to develop a script that was a time travel script that was really influenced by First And Last Men by Olaf Stapledon, which was a history of human evolution for a billion years going forward.

ALLAN SCOTT (Writer, Don’t Look Now)

Jerry Isenberg, who was the producer at that time, brought us in. We came out and met with him and Gene. We talked about the project and I think the only thing we agreed on at the time was that if we were going to make Star Trek as a motion picture, we should try and go forward, as it were, from the television series. Take it into another realm, if you like. Another dimension. To that end we were talking quite excitedly about a distinguished film director and Phil Kaufman’s name came up. We all thought that was a wonderful idea, and we met with him. Phil is a great enthusiast and very knowledgeable about science fiction.

PHILIP KAUFMAN (Director, The Right Stuff)

I had done White Dawn for Paramount and it wasn’t a big hit, but it was well regarded, so I got the call from my agent who thought I wouldn’t be interested in doing it. But the minute I heard what it was, that they wanted to make a $3 million movie of an old television series they thought would be worth reviving and there was a certain fan base, I knew I was interested. It wouldn’t have ordinarily been something that would interest me if it didn’t have all of these interesting situations, which I didn’t feel were that well executed on the TV show, by necessity.

ALLAN SCOTT

We did a huge amount of reading. We must have read 30 science fiction books of various kinds. At that time we also had that guy from NASA who was one of the advisors to the project, Jesco Von Puttkamer. He was at some of the meetings, and Gene was at all of the meetings.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

I met with Gene and I looked at episodes with him and we talked about all sorts of things. Somehow through the whole process I must say Gene always wanted to go back to his script, that he always wanted to really just do another episode with a little more money. Paramount wasn’t interested in that, because they’d already turned it down. But in the process of working with Jerry and Gene, we got them to commit to a $10 million movie, which was a good amount of money in those days.

GERALD ISENBERG

Phil was thinking 2001. He wanted to make another great movie, like the way 2001 explored the future and an alternate realities. That’s where he was going.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

Whatever the requirements of Sixties television were, they were really lacking in a visual quality and in all those things that a feature film in science fiction needed to have. I felt that those elements were in there, if properly thought out and expanded, and could be a fantastic event. We knew what the feature films in science fiction had been prior to this: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes, a few of these things that were wondrous adventures.

GERALD ISENBERG

David [Picker] believed Phil was a talented filmmaker and he is. He’s made a couple of great movies and won Academy Awards. And a real thinker. We sat in a room and he basically talked to us about the Star Trek audience and who the characters are, who the most important characters are, and who is the center of Star Trek and it’s Spock. You can take any other character out of that series and the series is the same. Even Kirk. You just replace him with another captain. But Spock is the center of that series. That character represents the essence of what that show is about.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

It was an adventure through a black hole into the future and the past and all; there were more relationships really developed beyond just the crew relationships. Kirk was to have an important role but not the center; the center was Spock, a Klingon, a woman parapsychologist who was trying to treat Spock’s insanity [he had gotten caught in his pon farr cycles] and there was going to be sex, which the 60’s series never had, but we were here at the end of the 70’s and we’re in a world where great movies were being made and the times were really ripe for expanding your mind.

GERALD ISENBERG

Leonard’s basic feeling was until he sees a finished script that he wants to do, whatever you want to do is fine. By that time in his life, Star Trek was a source of money for him through the appearances and everything else, but he was refusing to have that be his career and his image and his life. He was into writing. Leonard is a true Renaissance Man, he’s a writer and a photographer, a poet, he’s an amazing human being. So with the Spock character, of course, he represents the great conflict between reason and emotion, inherent in that person, so the whole Star Trek cast was a nice add-on, but the central conflict existed completely within Spock.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

Don’t forget, both Nimoy and Shatner were not going to participate in the feature when it first happened. There were some contractual problems they were having. I think I met Shatner briefly, but Leonard Nimoy and I got along great. I thought he was brilliant and after it was cancelled, I cast him in Invasion of the Body Snatchers and took some elements of Spock for the film. In the beginning, he is the shrink Dr. Kibner who is warm and trying to heal people, the human side, and then he turns into a pod which is the Vulcan side. Instead of pointy ears, I gave him Birkenstock sandals.

ALLAN SCOTT

Once we started working on the project with Phil, we were told that they had no deal with William Shatner, so in fact the first story draft we did eliminate Captain Kirk. It was only a month or six weeks in that we were called and told that Kirk was now aboard and should be one of the leading characters. So all of that work was wasted. At that time Chris and I would sit in a room and talk about story ideas and notions, and talk them through with either Phil or Gene.

GERALD ISENBERG

We sent Gene the first draft and he was not happy at all, but neither were we. He thought we were making a mistake in dropping Kirk. He basically took the position that we were not helping this franchise.

ALLAN SCOTT

Without any ill feeling on any part, it became clear to us that there was a divergence of view of how the movie should be made between Gene and Phil. I think Gene was quite right in sticking by not so much the specifics of Star Trek, but the general ethics of it. I think Phil was more interested in exploring a wider range of science fiction stories, and yet nonetheless staying faithful to Star Trek. The was definitely a tugging on the two sides between them.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

Gene was a great guy, but it was a little bit of the Alec Guinness syndrome in Bridge Over the River Kwai. He built a bridge and he didn’t want to be rescued and he couldn’t see anything other than what he wanted it to be. I thought science fiction should go forward and I thought that the order was to go boldly where no man has gone before, but Roddenberry wanted to go back.

ALLAN SCOTT

The difficulty was trying to make, as it were, an exploded episode of Star Trek that had its own justification in terms of the new scale that was available for it, because much of Star Trek‘s charm was the fact that it dealt with big and bold ideas on a small budget. Of course the first thing that a movie would do, potentially, was match the budget and the scale of the production to the boldness and vigor of the ideas. We spent weeks looking at every single episode of Star Trek and I would guess that pretty much every cast member came by and met us.

Among those involved with pre-production on the film were visionary James Bond production designer Ken Adam and Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica conceptual guru, Ralph McQuarrie. Star Trek continued to remain an obsession for Gulf & Western’s chairman, the legendary Charles Bludhorn, whose daughter, Dominique, was a devoted fan of the series.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

Ken Adam and I became good friends and we had that sense of making Star Trek a big event with this sense of wonder and visuals. I got to know Ralph McQuarrie through George Lucas and Ralph came aboard and starting designing things. London was cheap at the time and Ralph and Ken were in London. I’d been reading a lot of Olaf Stapleton.

This was all before Star Wars when I went to London scouting with Ken Adam, looking for locations. They had pulled the plug on Star Wars. Fox and all the people in London were laughing at what a disaster it was. George and his producer, Gary Kurtz, had gone on with the last couple of days with cameras to hastily try and piece together what they knew they needed to finish the movie.

So there was this mood out there that Star Wars was going to be a disaster. I knew otherwise; I had seen what George was doing and had been to what became ILM in the Valley and had spoken to George about that when we were working on the story for the first Raiders of the Lost Ark together. It was a sense of storytelling of what science fiction could be that George was into. That was brilliant and excited me.

I’d been in touch with him while he was shooting Star Wars, and I think George possibly had tried to get the rights to Star Trek prior to his doing Star Wars. I knew there was something great there. The times were crying out for good science fiction. Spielberg was also developing Close Encounters at that time, but Paramount didn’t really know what they had. It was to Rodenberry’s credit that he and the fan base had convinced them that a movie could be made, albeit on the cheap, and I didn’t want to do that, nor did Jerry.

Bryant and Scott turned in their first draft on March 1, 1977. It was Kaufman’s hope to cast legendary Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune as the Enterprise’s Klingon adversary, which could have been the greatest Star Trek villain in the franchise’s history, exceeding even Khan. But it was not to be.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

I had loved the power of those Kurosawa movies and The Seven Samaurai. If any other country other than America had a sense of science fiction, it was Japan. Toshiro Mifune up against Spock would have been a great piece of casting. There would have been a couple of scenes between the two of them, emotion versus Spock’s logic mind shield, trying to close things off, and having humor play between them. Leonard is a funny guy and the idea was not to break the mold of Star Trek, but to introduce it to a bigger audience around the world.

GERALD ISENBERG

We weren’t thinking this is a franchise and we’re going to do eight movies, we were thinking we would make one good movie. Star Wars launched as a franchise and nowadays you look back and think that everything is a franchise. What we would have ended up doing is a version that was essentially Star Trek, but not the Star Trek that was the series because we would have focused on Spock and his conflict and being human and what being human is. And that’s really what 80% of the Star Trek episodes are dealing with: being human. We were not trying to perpetuate the Star Trek franchise at that time. No one was.

In the script, the crew searches for Kirk and discover him stranded on a planet where they must face off with both the Klingons and an alien race called the Cygnans, eventually being thrust back in time through a black hole to the dawn of humanity on Earth where the crew themselves are revealed as the Titans of Greek mythology.

ALLAN SCOTT

I truly don’t remember anything about the script, except the ending. The ending involved primitive man on Earth, and I guess Spock or the crew of the Enterprise inadvertently introduced primitive man to the concept of fire. As they accelerated away, we realize that they were therefore giving birth to civilization as we know it.

I also know that eventually we got to a stage where we more or less didn’t have a story that everybody could agree on and we were in very short time of our delivery date. Chris and I decided that the best thing we could do was take all the information we had absorbed from everybody, sit down and hammer something out. In fact, we first did a fifteen or twenty page story in a three-day time period. I guess amendments were made to that in light of Gene and Phil’s recommendations, but already we were at a stage by then that the situation was desperate if we were going to make the movie according to the schedule that was given to us. We made various amendments, wrote the script, went to the studio with it and they turned it down.

PHILIP KAUFMAN

I still remember the night when it was getting very close. I was then writing and I stayed up all night, but I knew I had a great story. I remember how shaky I was trying to stand up from my writing table and I called Rose, my wife, and I said “I’ve got it, I really know this story,” and right then the phone rang. It was Jerry Isenberg saying the project’s been cancelled. And I said, “What do you mean?” and he said, “They said there’s no future in science fiction,” which is the greatest line: there is no future in science fiction.

Excerpted from The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years © Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman, 2016

Edward Gross is currently executive editor, U.S., for Empire Magazine‘s site, as well as a regular contributor to SciFi Now. He has also authored numerous nonfiction books, including Rocky: The Complete Guide and X-Files Confidential.

Mark A. Altman is co-executive producer of TNT’s hit series, The Librarians. He is a writer/producer for film and television whose movies include the beloved cult classic, Free Enterprise, starring William Shatner and Eric McCormack, as well as Agent X, Castle and Femme Fatales. He has been a journalist for such magazines as The Boston Globe, Cinefantastique and Geek among others.